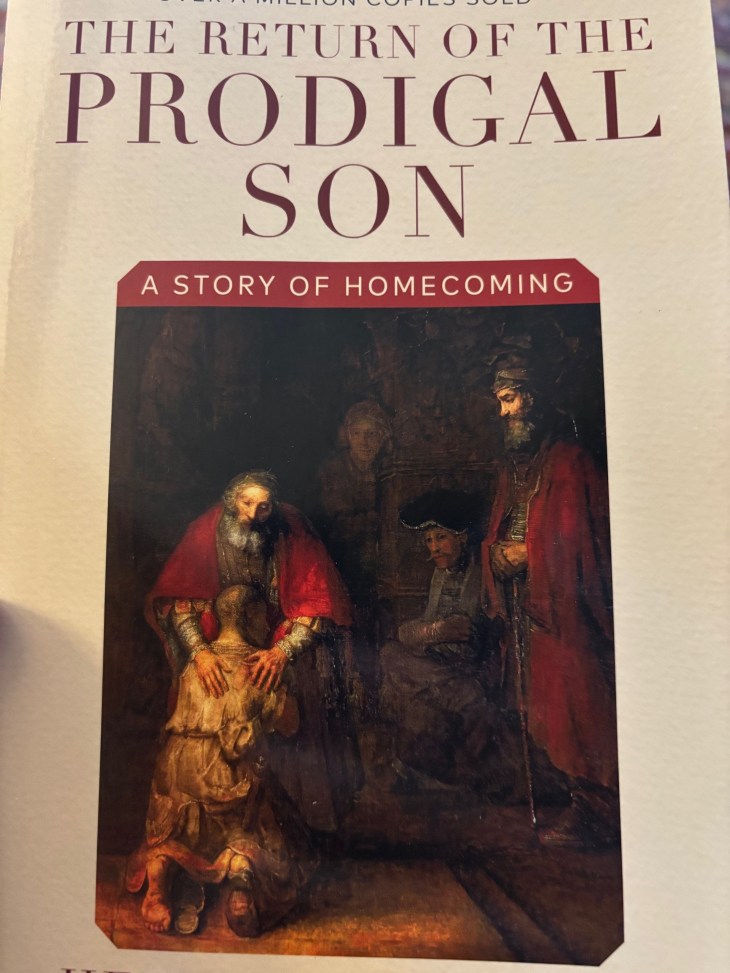

A book was recommended to me in May that I just now got around to reading: The Prodigal Son, by Henri Nowen. The book is a very thorough, very detailed examination of Rembrandt’s painting, “The Return of the Prodigal Son” [pictured above, on the book’s cover]. Even so, at the same time, the book is not really about the painting; instead, what it is really about is Nowen’s own homecoming to God, as he chronicles his own spiritual journey, and his periods of identification with the younger son, the elder son, and ultimately, the father.

Nowen’s insights are revealing and rich, and continually invites the reader to engage in her own self-reflection, reflecting on her own journey with God–her own identity, and her relationship to God and others. It is challenging, encouraging and deeply prayerful. So much so, that it prompted me to want to do a little blog series on several of the themes he raises, each of which is worth its own short reflection.

Those will start next week.

In the meantime, Nowen’s book also got me wondering if there is a particular painting with which I have had a similar love affair, analogous to what Nowen has with “The Prodigal Son.” I was so impressed with how his engagement with this painting lasted over decades, and only deepened over time. It reminded me the way one of my mentors felt about Augustine’s Confessions. It was a book she read and re-read regularly throughout her life, each time finding something new, and each time finding new resonances with her own life and experiences.

I can’t really say that I have found such an artistic touchstone— have you? A painting, a song, a book, a movie? I haven’t found anything that really compares to what Nowen, but I do have two paintings that are at least in the ballpark.

The first one is He Qi’s “Woman Caught in Adultery.”

This is a picture I’ve had in my office for over a decade, and I have written about it, preached about it, and prayed with it more times than I can count. And, similar to what Nowen observes about “The Prodigal Son,” it also contains different characters with whom I can identify at different times: the men with the stones, ready to torture and kill a sinner whom they have judged and condemned; the woman herself, naked and vulnerable, and utterly alone; and then of course, Jesus, who puts his own body between the victim and her accusers.

At various points in my life, I have been all of those people–and if I am honest, the Pharisees more times than I would like to admit.

But ultimately, for me, this picture is pure gospel–a vivid reminder of the lengths God will go to protect and preserve the most needy and desperate, a vivid reminder of the God who put his own body on the line to save other bodies: broken, shamed, and helpless. This is what salvation looks like. This is what my savior looks like.

The second picture is one I have not known nearly as long, and don’t know nearly as well, but the image is haunting and made a very deep impression on me the first time I saw it: ‘The Annunciation,” by Henry Ossawa Tanner.

I am an incarnation Christian, and by that I mean that the focus of my personal relationship with God, and my understanding of salvation, is deeply rooted in the Christmas miracle–Emmanuel, God-with-us. While Christ’s dying and rising obviously are a central piece of who Jesus is, for me, his birth and life are what I hold most tightly in my heart. Love incarnate, love come down, love drawn near, divine love inextricably entwined in the physical cosmos–that speaks salvation to me more deeply than any image of the cross.

So, the annunciation and Mary’s response to it is a critical scriptural witness for me: Mary’s yes, and her song, the Magnificat, which proclaims her trust in God, and her willingness to partner with God, in spite of her reservations. And not only that, but also her gratitude at being truly seen and valued by God, and being entrusted to bear the savior in her own body.

I seek out paintings of the annunciation every time I am in a gallery or museum, and there certainly are more of them than I can remember. But this one is my favorite.

I love it because it shows Mary‘s vulnerability, her poverty, her apprehension, and her bewilderment as she tries to process the impossible. I can relate to feeling some version of those emotions in the face of the work God has called me to do as well, and so my heart warms at this Mary, who is unsure of herself, doubting her worthiness, but trusting all the same that God will give her the strength, the confidence, and the ability to live into the reality God has announced to her. And, indeed, ultimately, she will rejoice as she becomes the woman God always knew she was. If Mary can, maybe I can as well.

I’m curious to follow along with your interactions and insights with this work. The pastoral team I work with read this as a group study last year and raised our own questions and wondering. Initially, no, I can’t recall a piece of art being so evocative or provocative in my own experience, and I really struggled to appreciate what Nouwen was trying to get at. If there were no title to this piece of art, I would not immediately experience as “The Prodigal Son” story.

LikeLike