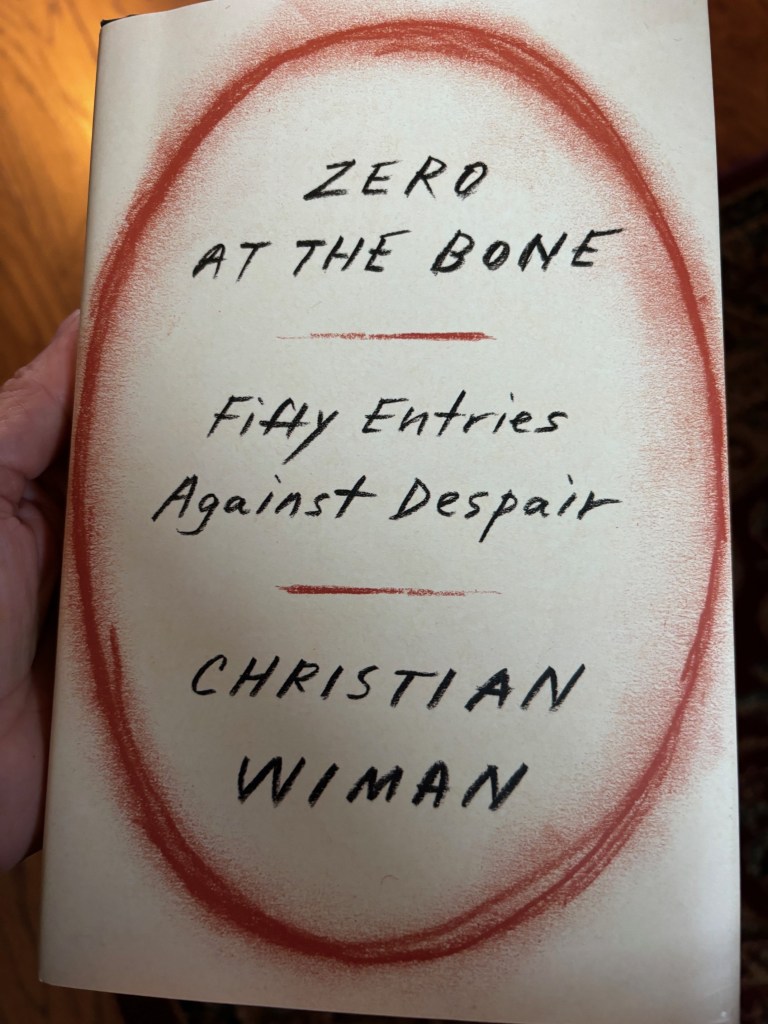

I read this book after reading an article about it in The New Yorker. Wiman is a poet, and is fighting a rare form of cancer. He is still alive beyond when the doctors all said he should be dead. In this book, he offers poems, personal reflections, quotes and other short meditations that combine a stubborn [if unconventional] Christian faith, an in-your-face staredown with death, and what I suppose could be called hope, if you squint when you look closely. They may be entries against despair, but they are certainly entries that feel the presence of despair breathing down the neck.

I have to be honest, it was a little grim for my taste, and his poetry doesn’t resonate with me as it might with you or others. So, I can’t go as far as recommending the book. However, the writing is very good, of course, and there were certain sections that did really strike me.

In one such section, number 6, “Issues of Blood,” he talked about his dog, Mack, whom he describes as a little strange–“odd and nervous.” They took him to the vet at one point, and found out that he had been living with bullet inside of him. He writes,

I can’t overstate how disturbing this news was to us. It’s not just the obvious disgust: to think of some miserable man–because, of course, it had to be a man–taking aim at this utterly docile, and probably mentally impaired dog, and blasting away. And then to think of Mack crawling off to die somewhere and then, somehow, not dying–for Mack is not only docile, but as our vet has told us, preternaturally tough….But it wasn’t just the act itself that disturbed us. No, what was really gut-wrenching, what left us both stunned and tearful in our kitchen the day we talked to the vet on the phone, was thinking about Mack carrying around this memento of that violent moment for all these years…to think of that sweet odd dog, all the while dragging around that unspeakable–in both senses of the word–pain.

And then he connects that story to the story in Luke about the woman suffering from the years of hemorrhages, saying that his experience with Mack made that story of her years-long suffering and pain real to him in a way it had never been before.

I also liked this quote from Katie Farris; I saw hope there:

“Why write poetry in a burning world?

To train myself, in the midst of a burning world,

to offer poems of love to a burning world.”

Number 37, “The Rock and the Rot,” is a sermon in which he talks about a “calling,” and he describes it as a “restlessness,” a “void that you can never quite fill” [Augustine would understand]–a voice from God that asks, “Who are you, really?” He relates that to Jesus’ question to his disciples, “Who do you say I am,” and concludes, “There is no one answer to Jesus’s question, and yet you must wager everything upon it.”

Finally, in number 49, “The Cancer Chair,” he writes, “Miroslav says some thinkers believe all existence is intertwined and some believe there is a crack that run through creation. For the first group the task of existence is to match one’s mind to that original unity. For the latter the task is one of repair, resistance, and/or rescue.” Here is his response to that idea:

Predictably, I find myself in both camps. I think all creation is unified; the expression of this feeling is called faith. And I think a crack runs through all creation; that crack is called consciousness. So many ways to say this. I know in my bones there is no escape from necessity, and know in my bones that God’s love reaches into and redeems every atom that I am. I believe the right response to reality is to bow down, and I believe the right response to reality is to scream. Life is tragic, and faith is comic. Life is necessity and love is grace.

This is looking into the abyss but not jumping in, staring despair in the face and not blinking.